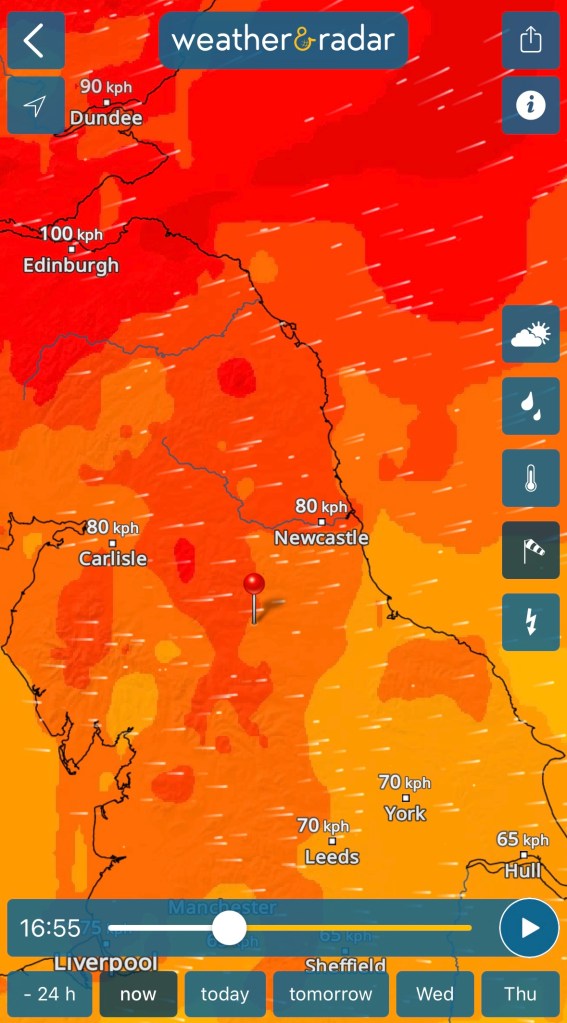

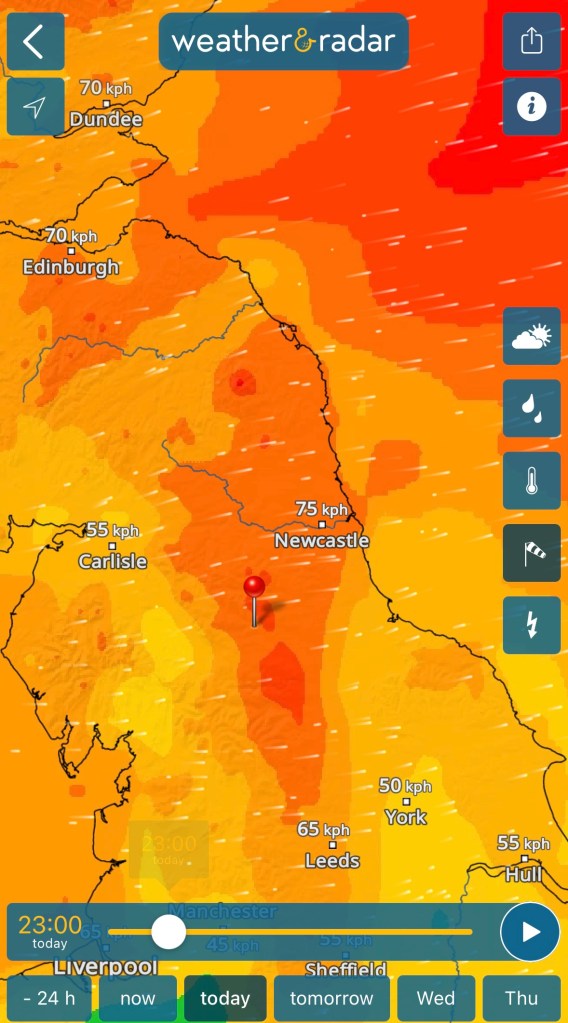

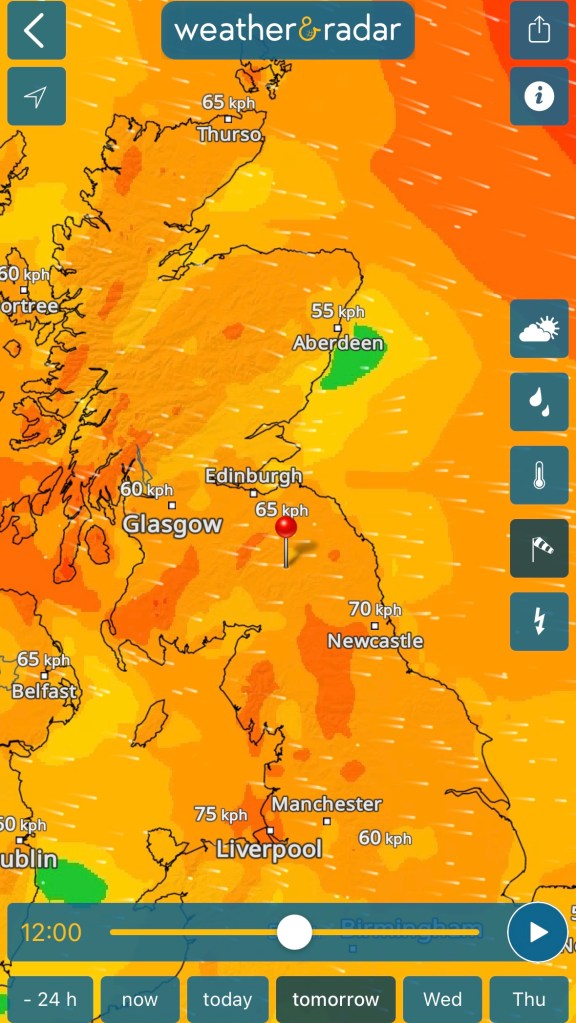

When I checked my iPhone on Monday morning after just two hours of sleep, I thought the weather app had frozen. The wind maps for both Monday and Tuesday seemed identical: a solid mass of red and amber indicating gusts of up to 80kph. Hours later I understood the truth — the app was fine, the forecast just didn’t change materially. Storm Floris was stuck over northern Britain, making Yad Moss and southern Scotland impassable.

When London Edinburgh London 2025 was cancelled, I was both gutted — months of preparation lost — and relieved that the decision to ride into dangerous winds was taken out of my hands.

Bizarrely, what followed over the next two days turned out to be one of the best cycling experiences in a very long time. I followed the LEL route back south, covering a total of 1030km since my start in Writtle on Sunday morning. Relieved of any time pressure, I got completely into my stride and was “in the zone” for days.

The camaraderie between riders seemed even better than normally, the kindness and support from volunteers was ever more special. Everyone seemed to be smiling in the face of adversity. Days after making it back to Writtle, I was still glowing.

London Edinburgh London 2025 must have been the best ‘cancelled’ ride in the history of cycling. Quickly relabeled “London Floris London”, it was a mass application of the principle that “when life gives you lemons, make lemonade.” The vast majority of riders shortened their ride and had a jolly good time riding south and stopping at the more southern controls. The volunteers played a blinder anyway.

The cancellation was of course frustrating. I had spent more than seven months preparing for these five days of cycling, using a week of holiday and spending hundreds if not thousands of euros on travel, food, kit and accommodation during preparation as well as the actual event. In the weeks before the start, I could hardly think of anything else. And over the first one and a half days and 517km, my ride had gone much better than I had dared to hope.

All riders I talked to during and after the event accepted the decision to cancel and thought it was the correct one. But on social media, some participants expressed reservations, pointing out that the PAID for the event, were bereft of the chance to complete the route and thought they had failed.

However, Ian McBride, the only rider quick enough to ride the whole route, wrote this on Facebook about his ride in Scotland:

“I was blown off the road twice just before Moffat. I had to walk two small parts as I couldn’t ride them. The end of the valley was a wind funnel. I was actually frightened on a few occasions. I was hoping every white van was an LEL van coming to pick me up saying it was all abandoned. I only carried on because I had no choice, there was nowhere to hide from it all. Trees were down on the road and small branches and stuff were flying all over the place. My return over Yad Moss 30 hours later went from sunny to very windy, some dangerous zigzagging all over the road, every stitch of clothing on again, and coming down to the bottom shaking cold and wringing wet. I think, sadly, the right choice was made. “

My ride

I was travelling to London with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. I finished LEL in 2017 but did not make it to the start line in 2022 due to an ill-timed Covid infection. But I was the LEL volunteer coordinator and had spent a lot of time on that in the run-up to the event, and also volunteered at start and finish. Due to a new job and a loss of volunteering mojo, I had resigned from that role some 14 months before the start of LEL 2025.

The start and finish this year was a new one and quite spectacular: Writtle College, a sprawling university campus with its own bar and on-site accommodation close to Chelmsford some 50 km north-east of London. I ran into many familiar faces from the British and German long-distance cycling community, which was fun.

I was fortunate enough to have a room right at the start, which was very convenient. However, I did not sleep well during the final night before the start – a habit – and was wide awake from 4am, almost two hours before my start time. A UK cycling friend – Greame – who was volunteering at the start cheered me up as he was directing riders with a laser sword. I did not expect to hallucinate even before the ride.

I started with Steffen, a German cycling friend I have been riding with a lot in recent years. We had agreed not to try to religiously stick together but to approach the ride as ‘free agents’. Normally we ride at roughly the same pace, but Steffen dropped me immediately as he was on fire. I was only going to see him again three days later on the return leg.

Steffen was not the only one who was faster than me. Basically everyone else was too, which I found surprisingly unsettling. I know I am a slow rider – but was I so slow? Was there something wrong with me? Why did I not catch up riders from earlier start groups? In an attempt to calm me down, I used one of the last resort tools and dbegan talking to myself. “Olaf, you know how to do this.” “You’ve done this before.” “You got this.”

I also concluded that while many riders must be much fitter than me, others were clearly punching above their weight and were going to pay the price for going too fast later. “We will talk again later!,” I started to tell myself when I got passed once more.

My first highlight was after 60km when I met Hans-Peter and Hendrik, two German friends who were volunteering and marshalled a hairy roundabout. Seeing familiar faces and chatting to them briefly really cheered me up.

Things got even better at the first control in Northstowe: even more familiar faces among the volunteers, some really good hot food, and an enchanting welcome from the female marshall at the entry to the control who was welcoming every rider with a cheerful and friendly “Welcome to Northstowe”.

I was in and out of the control within 20 minutes. On the way to Boston, I finally found my Audax mojo. I finally joined a few groups who were going at a convenient speed which was very helpful as we faced annoying crosswinds in the Fens. At the second control in Boston,I had covered 192 km in just under 9 hours, including stops. I enjoyed a fantastic vegetarian curry at the control and again was back on the road in 25 minutes again. While I was going more slowly than most other riders, I kept my breaks short and hence the same people started to pass me time and again after every control.

Some already appeared to be struggling while I was feeling increasingly confident. The beautiful Lincolnshire Wolds mountains were a welcome change to the boring flatlands, and at Louth, the welcome from the volunteers was even more spectacular than in Northstowe. We were greeted with small street party in front of the control. I briefly chatted with the chief controller in Louth, Damon, who is one of the funniest people in the whole LEL crowd before hitting the road again.

The two stages between Boston and Hessle, with Louth in between, were short with just 60km-ish each, and no big challenge. On Humber Bridge, one of the ride’s iconic landmarks, one of the LEL volunteers shouted “Olaf!” when I came past. It was Manfred, who I had briefly met at the start and was a mate of a Dortmund-based cycling friend. He was part of the team of roaming volunteers. His next task after bridge services on the following day was running the pop up café in Alston on the other side of Yad Moss, and we agreed to meet again there….

On the outskirts of Hessle, when I was riding into the dusk, a local guy stood by the roadside and clapped. The same chap was standing there and kept clapping two days later on my return trip. Impressive!

During the first day, I was constantly weighing my options for the night. I had booked a hotel room with 24 hours access in Malton as I feared the control might get overrun and I am not the biggest fan of the Audax dormitories in the first place.

As the time limit on LEL with a minimum speed of 12 kph is quite generous, I originally planned to sleep up to 4 to 6 hours in the hotel. But the weather forecast suggested that this was not a smart idea. The wind was going to get bad in the course of Monday, and the exposed section of Yad Moss was likely to get impassable. Should I ditch the hotel and ride through the night to Richmond in an attempt to make it across Yad Moss before the storm kicked in properly? Or should I wait in Malton until mid-day on Monday, hoping to make it to Yad Moss after the storm had gone through?

Every option had its pros and cons. After pondering for hours, I eventually decided to use the hotel room but limit myself to just two hours of sleep. I knew that tiredness can hit me quickly and out of the blue. Getting “the dozies” somewhere between Malton and Richmond (km 467) with no sleep options seemed risky, and could result in a very unpleasant night. And I also realised that even if I made it to Richmond during the night, there was no point in trying to ride even further as I then needed a brief laydown. As I needed to sleep anyway, why not use my hotel bed instead of a dorm and also have a quick shower?

It was the right decision. I arrived at my hotel in Malton shortly before 1:30am, covering 374km in just under 20 hours including stops. It was briefly brutal when the alarm clock went off after just 2 hours at 4am, but I felt very relaxed and well recovered. After a quick breakfast at the control, I was back on the road with only a few other riders and in a good mood.

Shortly after leaving the control I found myself in the Howardian Hills – an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty which had been on the LEL route for years. It was still new for me as I had chosen a flatter alternative in 2017 when the route was not mandatory.

While I knew that the Howardian Hills were scattered with bizarre monuments, I was blown awa when I saw an obelisk at the peak of a beautiful rolling hill, followed by Pyramid Gate and Carrmirre Gate. At dusk, with a peculiar hazy lighting, the setting was surreal.

The buildings lacked any purpose apart from just being there to impress the visitors. The slogan that the local tourism agency has coined for Howardian Hills – a landscape like no other – is spot on. I was even more satisfied that I sleept for a couple of hours in Malton as I would otherwise have crossed the Howardian Hills in darkness.

Then it started chucking down. The heavy rain that was forecasted came a few hours early. I passed the pop up control in Rainton without stopping and was shortly afterwards caught up by a British female solo rider. We had briefly met before and chatted a bit but she was faster on hills. As the next 30km were flat, we were now going at the same speed and talked about everything from female cricket, the crisis of journalism and the weather. At one point during the morning she got a call from her husband and then needed to explain to her four-year old daughter why this wasn’t the ideal moment for a video call, which I found very sweet. As we were approaching the hills around Catterick Garrions and Richmond, I told her that “you will lose me at the next climb”, which was prescient.

The final miles to Richmond turned grim again as they were hilly, the rain restarted, and there was quite a lot of morning traffic. I was struck by a warning sign “Tanks turning” but could not be arsed to stop and take a picture. When riding past the garrisons, I was moved by signposts to memorials for units that fought at the Ypres lines and other theatres of war in the first world war, but again did not take a look as I just wanted to get to the control.

My plan was to get back on the road quickly to carry on to Alston. I briefly chatted with Peter Davies, the chief controller in Richmond, who told me that there might be “an announcement” at 10:30 am about the weather. Without any additional information, I understood that this was likely to mean that the ride might be suspended and riders won’t be allowed to leave the control. That was a scenario I tried to avoid. I told Peter that I had planned to leave between 10:20 and 10:30, and he responded: “Well, you better go then!” Off I went. (Later, when I was back in Writtle, I learned that it apparently was decided to allow about 150 to leave Richmond before the ride was going to be suspended to relieve some of the pressure on the control which was likely to be completely overcroweded in any type of lockdown.)

Apart from the wind, the weather was glorious at this point as the sun had come out. The vistas in the borders area were lovely, and I was feeling chipper. The wind continuously got stronger though and turned into a proper headwind, which slowed me down markedly. At some point my wife texted me to tell me the ride was officially suspended. I joked that the most dangerous bit of cycling so far had been the crossing of the A66 north of Richmond: a dual carriageway with lots of fast traffic and no roundabout. A rider from Malaysia who was crossing the road at the same time as I was rather unsettled: “I’m not used to this!”, he told me.

While I was expecting the suspension of the ride, I was still slightly perplexed when it acutally happened. I briefly stopped in a bus shelter to look at my options, realizing that carrying on was actually the only one. There were no restaurants or pubs nearby. My best bet seemed to be the pop-up café in Mickleton some 25 km north. I carried on and the wind was getting ever more stronger. In another bus shelter some 10km on, I met the Malaysian rider again and convinced him to join me on the way to Mickleton. We were now riding into a fierce headwind, and also had to go pedal up a gentle yet long climb. Covering the 15km to Mickleton took us 1.5 hours.

A few kilometers before the village, a white van came our way, informing us that the ride was suspendended and that there was food and shelter waiting for us at the village hall in a few miles. While I was already aware, it was still a very uplifting moment. The last stretch was through a wild romantic narrow gorge, turning it into one of the most beautiful sections of the route so far. I was so determined to make it to Mickleton that I did not bother to take any pictures.

I was quite relieved when I finally arrived at the village hall. The 45 km from Richmond had taken me an incredible 3.5 hours of cycling, including two brief stops at bus shelters.

The pop up café was tiny. Locals had also erected a marquee and both the hall and the marquee were pretty packed. Cyclistes were taking a snooze inside on airbeds, others were outside laying in the sun. I bought some lovely home-made food and used the opportunity to dry my shoes and other clothes which were already wet from the heavy rain in the morning.

By afternoon in Mickleton it was clear to me that the ride wouldn’t restart. The hall was overcrowded, blankets gone, and I dreaded a sleepless night. A local mentioned hotels in Middleton-in-Teesdale, just a couple of kilometres further on, and I managed to grab one of the last rooms.

That evening the cancellation was confirmed; instead of lying cold in the hall, I had a hot meal, shared a room with another rider, and slept eight hours. I set off next morning refreshed, backtracking my way to Richmond, enjoying the beautiful scenery and a tailwind that made me feel like being on an e-bike.

When I came through Mickleton again I realised that the whole village was decorated with cycles and scarecrows – apparently the local community had organised an LEL-themed scarecrow contest. It made me sad that all this effort was largely going to waste as only some 200 of the total 2200 riders would ever make it to the village because of the weather.

Shortly after arriving at Richmond, I had tears in my eyes for the first time. By accident, I had just arrived when Peter Davies was giving his farewell address to the Richmond volunteers, who had been working all out through the night and the morning. The control, which had 350 beds, at peak times during the night was populated by more than 1000 cyclists. Peter got very emotional and had tears in his eyes. So did I.

After some food – baked beans and bacon was the only food that was left – I cracked on towards Malton, having decided to follow the LEL route back to Writtle. I stopped at the pop up control in Rainton this time, buying a lovely soup, a sandwich and a coffee. One of the locals told me that they had only some 15 cyclists who were stranded there during the night, and all were taken home by locals and put up in guest rooms. How lovely!

I had planned to ride up to Hessle on the northern side of Humber Bridge, assuming that would be around 250 kilometers from Middleton. As I did not fancy a night in the dorm, and did not have any time pressure, I booked a cheap room at the Ibis hotel in downtown Hull. But at some point between Malton and Hessle, it dawned upon me that I had miscalculated the distance which in fact was only 200km.

I found myself in Hessle at 8pm on a wounderful day with a terrific tailwind and by no means wanted to stop. The ride to Hessle had been fantastic, as I had good company from a German rider and the scenery – in particular a narrow green valley – was gorgeous.

For the whole day, I had been “in the flow”: the rare and blissful mental state of fully being in the here and now. I was completely absorbed by my cycling and felt strong and happy. I could not cancel the room anymore but decided to carry on regardless. At Hessle countrol, I briefly chatted with Hans-Peter and Hendrik again, the roaming volunteers from Germany who were down to marshall the bridge but currently off duty. I also briefly talked to Graham, the head of the roaming volunteers who I knew from my 2022 volunteer coordination days. It was so good to meet familiar faces and have a natter!

Crossing Humber Bridge always is a highlight. On the southern side I bought a few sandwiches and sweets to brace for potential shortages at Louth and Boston. The controls in Richmond, Malton and Hessle were already running low, and I was expecting that I may have to ride through the night to Boston (110km from Hessle) if I could not find a bed in Louth.

The coming 3.5 hours of cycling were among the best night cycling experience in years.

The night was warm, dry and under a full moon, the roads in the Lincolnshire Wolds were effectively empty, with few other cyclists being out there. To the left, the horizon was illuminated by the gas flare of the Prax Lindsey oil refinery down by the Humber. An almost mystical atmosphere and quite a contrast to 2017, when I entered the Lincolnshire Wolds southbound also at night but in heavy rain.

I met two very strong Indian riders, one Indian military officer and the other his friend and former RAAM participant. Time flew as we chatted. It could not get much better than this.

The control in Louth was so full that I struggled to find a place to park my bike and needed to rearrange some other bikes first. When checking in at the control, I met Damon again who magically managed to find me an empty bed. But I was so excited and full of adrenalin that I struggled to get to sleep for at least half an hour. I woke up at 4am after just three or so hours, unable to get back to sleep.

I had an early breakfast before the queues started, and chatted with a number of volunteers including Jo, a roaming volunteer who I knew from 2022 when she also was part of the team. So nice to meet again, so much to talk about. Later in the morning, I met my German cycling friends Steffen and Bogdan, who had both arrived earlier and slept at the control.

Steffen and I left together, riding into a beautiful sunrise in the gorgeous Lincolnshire Wolds. In the Fens we had an annoying side wind that turned head wind at times, and the day turned sunny and rather hot. We teamed up with a group of Swedes on steel bikes, one of them riding a nice Mercian – the first and only Mercian I saw on the entire ride.

Arriving in Northstowe was lovely as I had long chat with George, the chief controller, and also for the first time since the start met Anja, another Frankfurt cycling friend.

I am still in two minds about the subsequent bit of riding: the route went straight through downtown Cambridge, which was chock-a-block with tourists. I also happened to come through during late afternoon peak traffic. The road surfaces, not great in general, were particularly bad in and around Cambridge. We saw a decent incident of road rage when a local cyclist, who got clipped by a car, kicked against the vehicle’s wing mirror. It was horrible. But bizarrely, it was wonderful at the same time. When I came past the insanely beautiful facade of King’s College, a young singer in front of the gate sang Abba’s “The Winner Takes it all”. I was so touched by her voice and the overall setup that I had again tears in my eyes.

It is hard to remember and name all the friends among riders and volunteers I met on that day: Bogdan, Anja, Peter, Colin, George, Ivan, Ian, Tim…. The most special one was Gordon: an old cycling friend from London and the nicest person on the planet. Gordon is part of a group of friends who we see of a week’s cycling holiday each year. Almost to the week, he is as old as my father who sadly passed away almost four years ago. When I rode up Mont Ventoux with Gordon in 2023, I struggled to stay on his wheel. He became an octogenarian this summer. I knew Gordon was volunteering at the final control before the finish in Henham, and he marshalled the incoming riders when I arrived. It was a very very special moment.

In Henham, Steffen and I met Isabel and Tobbe, a German couple from Dresden and we teamed up to ride the final 40km to Writtle, enjoying small and traffic free lanes into a balmy summer night. The setting at the finish was spectacular: dozens of riders were lingering outside of the registration, having beers and talking about the mutual adventure. It felt like one big party in a cozy beer garden. The snag was that the “Riders Return” bar was drunk dry in no time and we had to decamp to the local pub in Writtle.

My bike

By the look of it, my bike setup was largely unchanged compared to my first LEL in 2017: A Mercian Vincitore Special steel bike with a hub dynamo and mudguards. Compared to eight years ago, there were some three key upgrades though: a Supernova M99 Dy Pro light instead of the Edelux 2, tubeless tyres, and a hot-waxed chain. The bike ran flawlessly all week.

I was lucky that I had an early start time and kept pushing on the first day so I managed to get 1030km in, a good two thirds of the overall route.

Ironically, while LEL 2025 was cut dramatically short, is proved an old adage: Audax, as they say, is not about making a good time but having a good time.

My ride on Strava:

Day 1: Writtle to Malton

Day 2: Malton to Mickleton and Mickleton to Middleton

Day 3: Middleton to Louth

Day 4: Louth to Writtle