Carbon frames and wheels, electronic shifting, tubeless tyres – in cycling, there has been a never ending string of innovation in recent years and decades.

Today’s average road bike still has two wheels and a diamond frame, but is totally different in almost any detail from a bike 50 or 60 years ago.

However, when it comes to speed, does innovation really matter?

This question recently crossed my mind when I stumbled upon the historic results of the iconic Paris-Brest-Paris audax – a 1200 km cycling event that is older than the modern Olympic games.

While it was initially run as a professional race, it has been turned into an amateur event after the second world war and since 1948 has been taking place every four years.

The basic rules have not fundamentally changed: you ride from Paris to Brest and back, have to pass a number of control towns, and the maximum time limit is 90 hours.

With about 10000 meters of climbing, the event is neither particularly hilly nor really flat.

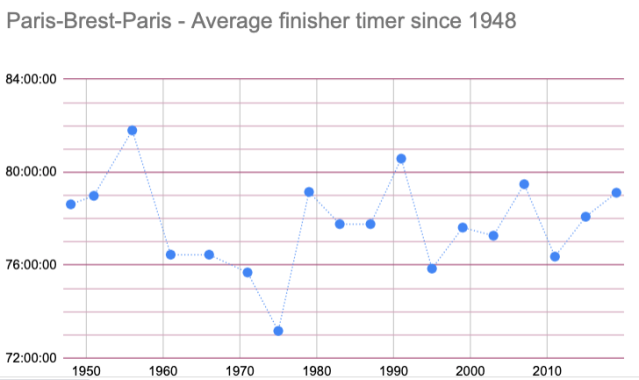

So what is the overall trend with regard to finishing times over the past 71 years?

Professional riders’ speed at the Tour de France went up by almost a third since the late 1940s to about 40kph.

Interestingly enough, this improvement is not at all mirrored for amateur riders taking part in Paris-Brest-Paris.

The average finishing time for a male rider since 1948 has been at around 78 hours, or around 15.3kph.

In 1948, long before Di2, hub dynamos and tubeless tyres with low rolling resistance were invented, the average rider came around in 78:37 hours, an average speed of 15.6 kph. In 2019, it took the average rider almost 20 minutes longer.

The fastest year was in 1975, when riders on average just took 73:10 hours – an average speed of 16kph. (It took me 87 hours in 2015 and 84 hours in 2019.)

The overall average, of course, can be a misleading yardstick, as it is influenced by the average riding speed as well as the time spent off the bike. So maybe people on modern bikes these days ride faster and get more sleep in return?

It’s really difficult to tell. A different potential explanation that seems plausible to me may be that the growing popularity of long-distance cycling has changed the selection of riders over time.

While there were only 205 participants in 1948 and just 3300 in 1991, the last edition saw a new record with some 6300 starters.

Moreover, these days’ riders come from all across the world and many from Asian countries struggle with the cold and wet northern European climate, with some 80 per cent of the 500 or so riders from India, China and Thailand failing in 2019.

Also, the details of the route changed a lot over time due to the increasing car traffic, and the main roads that were used in the past but are far too busy and dangerous these days may have been faster than the current routes.

Another explanation may be that riders who have enough time in hand deliberately take longer breaks to get additional sleep and to avoid arriving at night or in the early hours of the morning – as PBP is not a race, the finishing time eventually only matters for the rider’s own vanity.

A different data point to look at is the finishing time for the fastest rider, as those riders never really could afford to take long stops.

Interestingly, in the early years of modern-day PBP, between 1948 and 1966, there actually has been some meaningful improvement, with the finishing time falling by 13 per cent from 51:15 hours to 44:21 hours (or average speed rising from 23.4 kph to 27.1kph).

After 1966, however, this trend disappeared with the fastest rider finishing in 43 to 45 hours. From the mid-1990s to 2011, there even as a somehow rising trend which was reversed in 2015 when Björn Lenhard finishing in 42:26 hours and set a new record. But four years later the fastest rider took 1:20 hours longer while the route was some 12 km shorter, and the second and third best times were ridden in 1995 and 1975.

For me, this suggests that individual capabilities plus external factors like wind and rain on long-distance rides like Paris-Brest-Paris matter much more than the type of bike a person is riding.

Since the mid-1960s, the improvements in bicycle technology don’t seem to have been big enough to consistently trump factors like individual fitness, weather conditions and route choice.

Each PBP participant is spending hours after hours thinking about the optimal bike setup – but eventually the bike does not seem to matter that much.

This tallies with the results of a 2007 survey about the equipment of PBP participants. It failed to find meaningful correlations between a rider’s kit choices and his or her success rate:

“We found no consistent evidence that bikes with racing-oriented equipment provided a speed advantage over more completely equipped bicycles among riders with similar goals.”

The authors concluded:

“For the most part, randonneuring is a sport where outcomes are determined by the riders and not by the equipment. Other factors appear to be much more important than equipment choices.”

How is it possible that seven decades of engineering had so little if any influence on Audaxing speed?

First and foremost this probably shows what an ingenious and efficient machine the modern day bicycle is in the first place.

Secondly, many improvements in cycling technology focus on reducing weight. This makes sense if you are one of the best riders of your generation, perfectly trained and keen on winning the Tour de France. However, in long-distance cycling, the bike’s weight is less important than we normally think.

As Chris White points out on Ridefar points out,

“weight differences should be thought of as the percentage of the total system weight (rider + bike + equipment), not as a percentage of just the bike and/or the equipment.”

According to his calculation, reducing the bike’s weight by 1 kg only reduces system weight by just 1.2 per cent – this is based on the assumption of a 10kg bike, 8kg of equipment and a rider’s weight of 67 kg.

Chis estimates that reducing weight by one kilogram only saves 3 minutes per day.

Obviously, speed is not the only – and probably not the most important – dimension that matters in Audaxing. Comfort and safety are other important aspects. In particular with regard for lighting, there have been massive improvements over the last decade or two – think hub dynamos, LED lamps and durable batteries.

So while I admit that I am fond for classic steel bikes, even I would not fancy riding PBP on a 1960s bike next time.

Vielleicht nehmen die Fahrer heute einfach weniger Amphetamine? Das war doch bis in die 1970er noch mehr oder weniger de rigueur … und wird vielleicht durch die bessere Trainingswissenschaft heute nur unzureichend ausgeglichen. Ich glaube ja, dass viele alte Langstreckenrekorde, ob auf dem Rad, auf dem Motorrad oder im Auto, nur mit starken Wachmachern möglich waren.

Perhaps it’s balanced out by the lack of strong stimulates.

*stimulants

Thanks for the information!!

As you reference, it’s not a race.

Indeed, the faster I can go on the road, the more time I SLEEP — I am spreading my ride across the full 90-hour time allotment, targeting to finish with a couple of hours to spare “just in case.”

I’m not sure how any technical advances in the bike — which, for me, simply would result in more sleep time — would ever show in my finish time.

I’m not really sure that one can conclude much of anything at all from averaged finish time data. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯